Find a Document

How We Get Our Water: Infrastructure Serving Our Communities

Delivering water to Southern California homes and businesses is as much about infrastructure as it is about actual water. While Metropolitan is working hard to ensure the reliability of our imported water supplies and increasingly investing in local supplies, that is just the beginning. Bringing drinking water to your faucet takes hundreds of miles of aqueduct, dozens of high-powered pumps, a vast storage system of reservoirs and groundwater basins across the state, regional water treatment facilities, and an extensive distribution system of pipelines and service connections.

Bringing Water Across the State

About 20% of the water used in Southern California typically comes from the Colorado River. Another 30% originates in the Northern Sierra. The remaining 50% comes from a mix of what are considered local supplies, which includes the city of Los Angeles’ eastern Sierra deliveries as well as recycling, desalination and groundwater supplies. That means most of our water travels a great distance to get to our faucets.

It all started with the construction of the Colorado River Aqueduct. Metropolitan was formed in 1928 to build the aqueduct and bring water from the Colorado River, across the Mojave Desert, to Southern California. The 242-mile system includes open aqueduct, siphons, five pumping plants, reservoirs, and massive 16-foot wide tunnels that vary in length from 338 feet to 18.3 miles. Metropolitan has an extensive ongoing program to refurbish and maintain the CRA, ensuring reliability for decades to come.

Metropolitan later contracted with the state to help bring Northern Sierra water south through the State Water Project. The State Water Project is operated and maintained by the California Department of Water Resources and includes 34 storage facilities, reservoirs and lakes; 20 pumping plants; four pumping-generating plants; five hydroelectric power plants. It also features about 700 miles of open canals and pipelines, including the 444-mile California Aqueduct, which ranges from 50 - 110 feet wide and up to 32 feet deep.

Once State Project and Colorado River water reach Southern California, it must be distributed across Metropolitan’s 5,200-square-mile region. Some of the water is first treated at one of Metropolitan’s five regional treatment facilities before being distributed, and some is distributed as untreated water and purified later. Metropolitan's distribution system consists of 830 miles of large diameter pipelines and about 400 connections with our member agencies, which then distribute the water to their communities before it finally arrives at your tap.

Storing for the Dry Years

California’s naturally variable weather, which is being exacerbated by climate change, makes storage a critical element of Metropolitan’s ability to reliably deliver water to the region. It has become increasingly important that we take advantage of water when it is available and store it for times when it is not. That’s why Metropolitan has invested significantly in storage over the past three decades, increasing our storage capacity by 13 times. Some of that storage is in groundwater banking programs locally and throughout the state, some is in state reservoirs along the State Water Project and federal reservoirs along the Colorado River, and some is in Metropolitan’s own reservoirs.

Metropolitan Reservoirs

Our reservoirs not only provide supplies during times of dry conditions or drought, they also are in place for use in emergencies such as earthquakes.

Diamond Valley Lake, capacity of 810,000 acre-feet

Built in the late 1990s, Diamond Valley Lake is Southern California’s largest reservoir. Along with Metropolitan’s other reserves, it holds enough water to meet Southern California’s emergency and drought needs for six months. Located in Hemet in southwest Riverside County, it offers recreational opportunities to the public.

Lake Mathews, capacity of 182,000 acre-feet

Lake Mathews in southwest Riverside County is the terminal reservoir for the Colorado River Aqueduct and was built at the same time in the 1930s. Though there are no public recreation facilities at Lake Mathews, it is surrounded by approximately 4,000 acres of protected lands and reserves.

Lake Skinner, capacity of 44,000 acre-feet

Lake Skinner was completed in 1973 and feeds water to the Skinner treatment plant before it is delivered to Metropolitan’s member agencies. Located outside of Temecula, Lake Skinner offers a variety of recreational facilities.

Six smaller reservoirs, total capacity 32,000 acre-feet

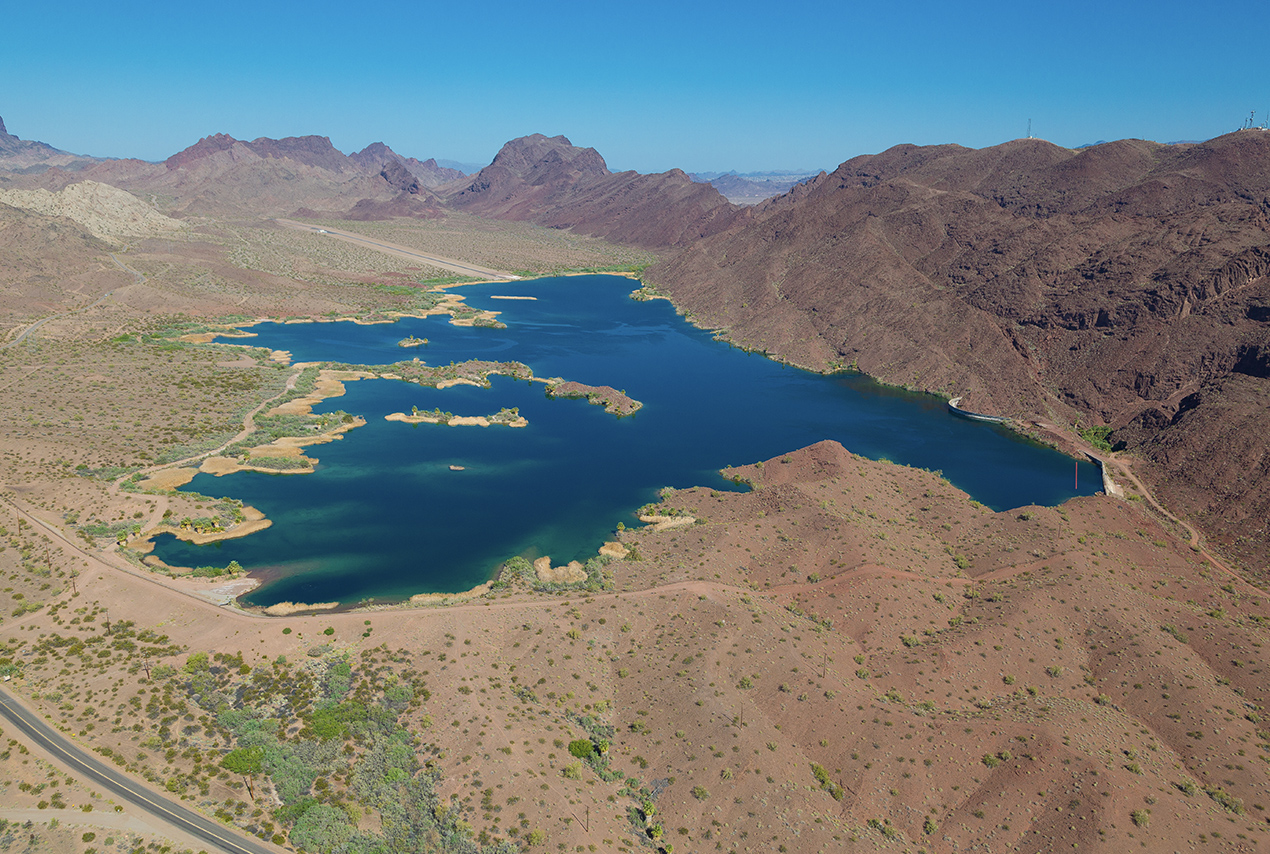

In addition to its three large reservoirs, Metropolitan operates six smaller regulating reservoirs: Copper Basin and Gene Wash near the start of the Colorado River Aqueduct, Live Oak, Palos Verdes and Garvey reservoirs in Los Angeles County and Orange County reservoir near Brea.

How Full Are These Reservoirs?

Get a snapshot of storage levels in key Southern California reservoirs, rain and snowpack data in the Sierra Nevada and the Colorado River, and a general understanding of Metropolitan’s water supply conditions with these reports:

Pumping Plants

While water flows through much of Metropolitan's service area powered by gravity, it takes five pumping plants along the Colorado River Aqueduct to ensure it reaches its final destination at Lake Mathews. These pumping plants combined lift CRA water supplies just over 1,600 feet, allowing it to flow by gravity west across the Mojave Desert. All pumping plants have nine pumps, each with a nominal rated capacity of at least 225 cubic feet per second. Once it reaches the region, Colorado River water flows through Metropolitan's entire distribution system and treatment plants by gravity, under normal operations. Read more.

W.P. Whitsett Intake Pumping Plant

The Intake plant is the starting point of the Colorado River Aqueduct supply and lifts water out of Lake Havasu 291 feet, from an elevation of 450 feet above sea level to 741 feet.

Gene Pumping Plant

The Gene plant is located two miles west of the Intake plant. The facility lifts water from Gene Wash reservoir 303 feet to Copper Basin reservoir, at an elevation of 1,037 feet.

Iron Mountain Pumping Plant

The Iron Mountain plant is 70 miles from Copper Basin and lifts water 144 feet.

Eagle Mountain Pumping Plant

The Eagle Mountain plant is 40 miles west of Iron Mountain and lifts water 438 feet to an elevation of 1,404 feet.

Julian Hinds Pumping Plant

The Hinds plant is 16 miles west of Eagle Mountain and has the highest lift of all the plants, 441 feet to an elevation of 1,807 feet.

Reducing Pumping Costs with Hydro & Solar Power

It takes a lot of energy to pump water 1,600 feet up a mountain. Pumping water along the CRA uses about 2 million megawatt-hours of energy a year. About half of this is met by Metropolitan’s allocation of power from Hoover and Parker dams. To offset the rest of our power costs, Metropolitan has built 15 hydroelectric plants throughout our distribution system.

Largely built in the late 1970s and early 1980s during that era’s energy crisis, the plants not only generate electricity, they also help control pressure within the distribution system. These 15 hydroelectric plants generate about 250,000 megawatt-hours of energy per year and have a total capacity of about 130 megawatts.

Metropolitan has also developed 5 ½ megawatts of solar power at our facilities. And we’re exploring other ways to further reduce our carbon emissions and stabilize energy costs through our Energy Sustainability Plan. That plan could include adding additional renewable energy to our portfolio, increasing our energy efficiency and storage, and load shifting to take advantage of solar power.

Here’s a snapshot of Metropolitan’s delivery and treatment system.

Operations Data

To access meter data usage and water sales information, use the links below to our Water Information System (WINS). If you have any issues, please contact, Phillip Furca at (213) 217-7123.